Audio Player

Audio Player

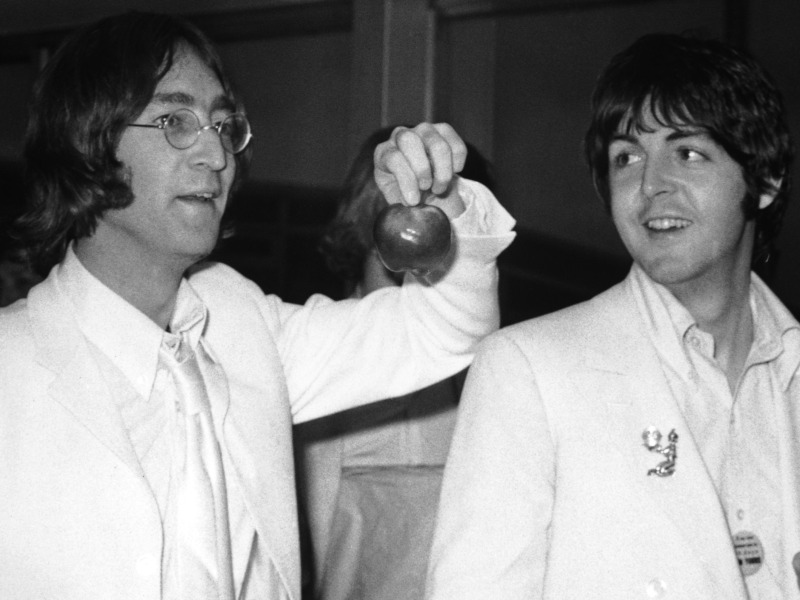

Ken Mansfield, the former U.S. manager of the Beatles' Apple Records, died on November 17th at age 85. Mansfield, who promoted the “Fab Four” on Capitol prior to being among the first on the Apple team, had worked with such legends as the Beach Boys, Buck Owens, Glen Campbell, Judy Garland, and many others before joining the group's personal label.

Starting with “Hey Jude,” Mansfield played a crucial role in promoting both the Beatles' music, as well as other Apple acts such as Mary Hopkin, James Taylor, Jackie Lomax, and Badfinger.

In 2018, Mansfield published his second memoir on his time with working with the Beatles, titled The Roof: The Beatles’ Final Concert.

Mansfield left Apple for MGM when John Lennon, George Harrison, and Ringo Starr appointed Allen Klein as the Beatles' manager in the spring of 1969 against Paul McCartney's wishes.

After his time with the Beatles, Mansfield worked in various capacities — including record production — for a number of artists, including Andy Williams, Waylon Jennings, Dolly Parton, Ray Stevens, Jimmy Buffett, Don Ho, the Everly Brothers, Nick Gilder, Paul Anka, the Flying Burrito Brothers, and David Cassidy, among many, many others. In 1992 while working as an exec at the BMG subsidiary Private Music, he was instrumental in signing Ringo Starr for his first new album in a decade, the 1992 comeback, Time Takes Time.

While discussing his mid-'60s promo days at Capitol Records, Mansfield told us that the Beatles were so massive that they not only blocked acts from other labels from hitting the top spots on the album and single charts — but even artists from the Beatles' own label: “They were always mad. Think about it — we had legitimate Number One records with other artists on our label; but they couldn't go to Number One (because of the Beatles' dominance), they could only go to Number Two. 'I had a Number One record' (or) 'I had a Number Two record' — which one sounds. . . y'know, there's just that difference. So, we constantly had this problem. Y'know, it went further than just the airplay and the charts — it also went with the pressing plants. Here, an artist has a record out, a Beatles record comes out, it just stopped our pressing plants. All we could do is press Beatle records.”

Along with an eyewitness account of the Beatles performing live for the final time as a unit, in his memoir, The Roof, Mansfield gave a personal account of what made the early months of the group's Apple Records so unique and groundbreaking: “I wanted to encapsulate the beginning of Apple and in and odd way, phase out the ending without defining the ending of Apple. Apple ended, basically, kind of after the roof. Y'know, that was kind of the beginning of the end. I didn't want it to be a bunch of facts, and a bunch of statistics; I just wanted people to see that it was real people. It was just this special place and I wanted to encapsulate that time period, I'm not trying to talk about all the time before the Beatles' stuff and the different albums — or anything. I just wanted to talk about Apple and then, the day of the roof was, like, the beginning of the end for me.”

Ken Mansfield told us it was a testament to the Beatles that they ended up with such a loyal staff: “I felt so honored to be invited inside their world and privileged, that a bunch of us had agreed that we would never write about our time with the Beatles. It's not because the Beatles said, 'Lookit, you're gonna be inside, you're gonna see some stuff, you're gonna know some stuff, we wanna be free to do. . . So you're gonna have to agree not to write or talk about it.' It was just something, we felt so privileged, we had so much respect. I have to tell you man, they treated me so good and so kind.”